General Information

Benchmark Instructional Guide

Connecting Benchmarks/Horizontal Alignment

Terms from the K-12 Glossary

- Angle

- Parallelogram

- Quadrilateral

- Rectangle

- Rhombus

- Square

- Supplementary Angles

Vertical Alignment

Previous Benchmarks

Next Benchmarks

Purpose and Instructional Strategies

In elementary grades, students identified and classified quadrilaterals, including parallelograms. In grade 7, students solved problems involving the area of parallelograms. In Geometry, students establish relationships between sides, angles and diagonals of parallelograms (including the special cases of parallelograms: rectangles, rhombi and squares), prove the theorems related to these relationships and use them to solve mathematical and real-world problems. In later courses, parallelograms play an important role in work with vectors.- Relationships, postulates and theorems in this benchmark should focus on, but are not limited to, the ones stated in Clarification 1. Additionally, some postulates and theorems have a converse (i.e., if conclusion, then hypothesis) that can be included.

- Instruction includes the connection to the Logic and Discrete Theory benchmarks when developing proofs. Additionally, with the construction of proofs, instruction reinforces the Properties of Operations, Equality and Inequality. (MTR.5.1)

- Instruction utilizes different ways students can organize their reasoning by constructing various proofs when proving geometric statements. It is important to explain the terms statements and reasons, their roles in a geometric proof, and how they must correspond to each other. Regardless of the style, a geometric proof is a carefully written argument that begins with known facts, proceeds from there through a series of logical deductions, and ends with the statement you are trying to prove. (MTR.2.1)

- For examples of different types of proofs, please see MA.912.LT.4.8.

- Instruction includes the connection to compass and straight edge constructions and how the validity of the construction is justified by a proof. (MTR.5.1)

- Students should develop an understanding for the difference between a postulate, which is assumed true without a proof, and a theorem, which is a true statement that can be proven. Additionally, students should understand why relationships and theorems can be proven and postulates cannot.

- Instruction includes the use of hatch marks, hash marks, arc marks or tick marks, a form of mathematical notation, to represent segments of equal length or angles of equal measure in diagrams and images.

- Students should understand the difference between congruent and equal. If two segments are congruent (i.e., PQ ≅ MN), then they have equivalent lengths (i.e., PQ = MN) and the converse is true. If two angles are congruent (i.e., ∠ABC ≅ ∠PQR), then they have equivalent angle measure (i.e., ∠ABC = ∠PQR) and the converse is true.

- Instruction includes the use of hands-on manipulatives and geometric software for students to explore relationships, postulates and theorems.

- Instruction includes discussing that the definition of a parallelogram only states that the opposite sides are parallel; anything else (e.g., opposite sides are congruent or opposite angles are congruent) is a property and needs to be proven. Students should understand that all parallelograms are trapezoids based on the definition within the K-12 Glossary.

- Instruction includes the connection to triangle congruence and the relationship between angles formed by a transversal through parallel lines when completing proofs about parallelograms.

- When the properties of parallelograms are introduced and proven, it is important to discuss the definitions of rectangles, rhombi and squares. Precision and accuracy are important when discussing the definitions of the special parallelograms. (MTR.3.1, MTR.4.1)

- For example, some possible discussion questions include:

- What makes a parallelogram a rectangle?

- What is the unique feature of a rhombus?

- Is a square always a rectangle?

- Is a square sometimes a rhombus?

- Is a rectangle always a square? Is a rhombus always a square?

- What are the properties of a parallelogram observed in a rhombus?

- For example, some possible discussion questions include:

- Instruction includes proving that the diagonals of a parallelogram bisect each other and that the diagonals of a parallelogram are congruent if and only if the parallelogram is a rectangle. Clarify that just having congruent diagonals will not be enough to identify a quadrilateral as a rectangle as this is also a property of isosceles trapezoids. The quadrilateral has to be proven a parallelogram to use this property to classify it as a rectangle.

- Instruction includes the understanding that properties of parallelograms apply to all parallelograms, including squares, rhombi and rectangles.

Common Misconceptions or Errors

- Students may think of squares, parallelograms, rectangles and rhombi as being exclusive to each other. A square is a rectangle and a rhombus.

- Students may think that parallelograms are not trapezoids. The K-12 Mathematics Glossary defines trapezoids as quadrilaterals with at least one pair of parallel sides. Therefore, all parallelograms are trapezoids.

Instructional Tasks

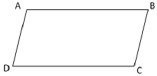

Instructional Task 1 (MTR.3.1)- Given parallelogram ABCD, prove that angle A and angle B are supplementary.

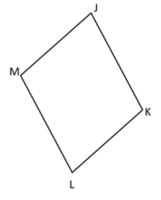

- Given quadrilateral JKLM with JK ≅ LM ≅ MJ.

- Part A. Draw the diagonal connecting points M and K. Determine and prove that two triangles are congruent.

- Part B. Using the congruent triangles from Part A, what is true about segments MJ and LK?

- Part C. Prove that quadrilateral JKLM is a parallelogram.

Instructional Items

Instructional Item 1- Given parallelogram WXYZ, where WX = 2 + 15, XY = + 27 and YZ = 4 − 21, determine the length of ZW, in inches.